World

Europe Is Still Buying Russian Oil, but It’s Now Harder to Track

WSJ Login: Russia ramped up oil shipments to key customers in recent weeks, defying its pariah status in world energy markets. One increasingly popular method for delivery: tankers marked “destination unknown.”

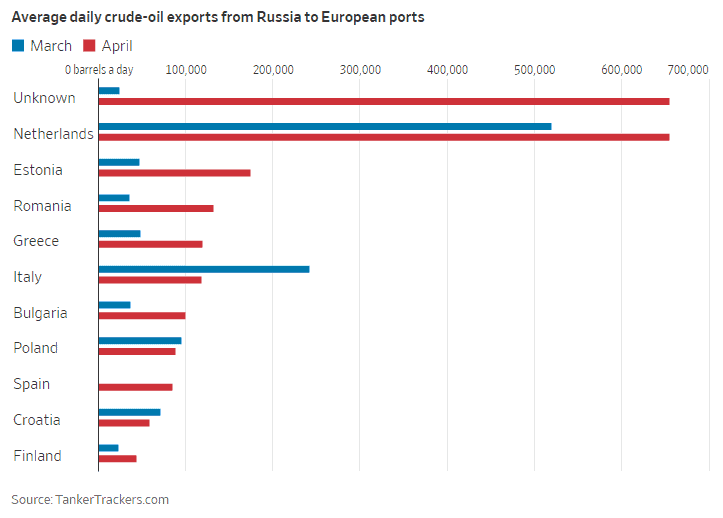

Oil exports from Russian ports bound for European Union member states, which historically have been the biggest buyers of Russian crude, have risen to an average of 1.6 million barrels a day so far in April, according to TankerTrackers.com. Exports had dropped to 1.3 million a day in March following the Ukraine invasion. Similar data from Kpler, another commodities data provider, showed flows rose to 1.3 million a day in April from 1 million in mid-March.

But an opaque market is forming to obscure the origin of that oil. Unlike before Russia invaded Ukraine, oil buyers are worried about the reputational risk of trading crude that is financing a government that Western leaders accuse of war crimes.

Get Financial Times and The Economist Digital 3 Years Combo News Save 77% Off

Oil from Russian ports is increasingly being shipped with its destination unknown. In April so far, over 11.1 million barrels were loaded into tankers without a planned route, more than to any country, according to TankerTrackers.com. That is up from almost none before the invasion.

One reason to obscure the origin of Russian oil is that countries desperately need the crude to keep economies going and prevent fuel prices from surging even further. But companies and oil middlemen want to trade it quietly, avoiding any blowback for facilitating transactions that in the end provide money for Moscow’s war machine.

The use of the destination unknown label is a sign that the oil is being taken to larger ships at sea and unloaded, analysts and traders said. Russian crude is then mixed with the ship’s cargo, blurring where it came from. This is an old practice that has enabled exports from sanctioned countries such as Iran and Venezuela.

The Elandra Denali ship was off the coast of Gibraltar last week when it received three loads of oil from tankers that left from the Ust-Luga and Primorsk ports in Russia, according to the vessel operators, people involved in the transshipment and two ship-tracking companies. The ship records show that it departed from Incheon, South Korea, and is planning to arrive in Rotterdam, a key refining port in the Netherlands.

Buy Fiancial Times and The New York Times Subscription Save 77% Off

New grades of refined products dubbed the Latvian blend and the Turkmenistani blend are also being offered in the market, according to traders, with the understanding that they contain substantial amounts of Russian oil, they said.

Oil sales for Russia are the lifeblood of the economy and government spending. The country has struggled to sell oil at the same volumes and prices as before the war, causing backups in its domestic oil industry.

The U.S., U.K., Canada and Australia have banned imports of Russian oil. The EU is more dependent on Russian energy, importing 27% of its oil from the country. European leaders have debated whether to impose an embargo as well, but have yet to act, as they balance the desire to isolate Russia without inflicting pain on their own economies through higher energy prices.

A popular grade of Russian crude known as Urals is being priced at between $20 and $30 below the Brent benchmark, according to traders. Before the invasion it was typically in line with the benchmark or a dollar or two below. Russia has struck some deals to sell oil to buyers in India.

Much of Russia’s oil is still being marked with clear destinations on shipping documents. Barrels bound for Romania, Estonia, Greece and Bulgaria more than doubled this month compared with March averages. Volumes also rose substantially for the Netherlands, the biggest buyer in Europe, and Finland.

Some buyers are rushing to get business done in anticipation of potential new restrictions, while others say they are executing deals struck before the invasion. Sanctions would force them to break those contracts.

Subscribe to New York Times Subscription (Digital 3-Years) Save 70% Off

“The fact that they are buying more than before the invasion suggests that it’s not just because of long-term contracts,” said Simon Johnson, an economics professor at MIT researching oil geopolitics and former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. “It’s also about cheap energy. Until there is a full embargo, this can go on.”

In recent weeks, oil majors and commodity trading houses including Royal Dutch Shell PLC, Repsol SA, Exxon Mobil Corp., Eni SpA, Trafigura Group and Vitol Group chartered ships to transport crude from Russian oil terminals on the Black Sea and Baltic Sea to ports in the European Union, according to Global Witness, a research and advocacy group working with the Ukrainian government, and Refinitiv data. The cargoes arrived in Italy, Spain and the Netherlands this month, the data showed.

A Repsol spokesman said that shipments received recently are tied to long-term obligations undertaken before the invasion. Shell, Exxon and Eni said they are transporting oil from Kazakhstan through a Russian port. Trafigura said it was trading less Russian oil than before the invasion. Vitol didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Shell said on April 7 that it would stop buying Russian oil in the spot market but that it is legally obliged to take delivery of crude due to contracts signed before the invasion. The company defines refined products to be of Russian origin if blends contain 50% or more, leaving the door open to trading products such as diesel if it contains 49.9% Russian oil or less.

Get New York Times Subscription and WSJ Digital 5-Years Combo, Save 77% Off

The Ukrainian government sent a letter to Shell CEO Ben van Beurden on April 13 in which it criticized this approach, stating that “the notion that any company will continue to bankroll Putin’s war machine through an accounting trick is deplorable.”

“It’s a national shame for many governments and institutions that are financing these aggressions towards us,” said Oleg Ustenko, an economic adviser to the Ukrainian president.

A Shell spokesman said the company’s “self-imposed restrictive measures go far beyond any European Union measures in place today.”

EU officials are drafting a plan for a potential embargo, but the timing is still under consideration due to the upcoming French election and pushback from Germany. An embargo would likely only be implemented over time. Some worry that traders are already working out ways to keep the oil flowing.

“Even if we see some kind of oil embargo from the EU, will they remember to sanction the tankers? More ship-to-ship transfers away from the coast, it’s a reasonable expectation,” Mr. Johnson said.